First Abstractions

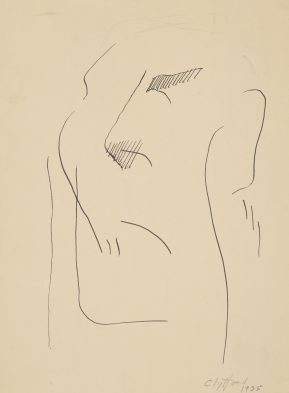

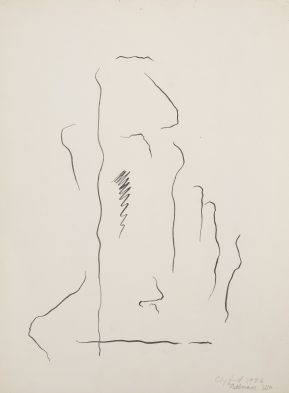

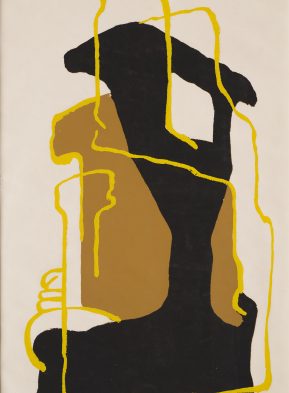

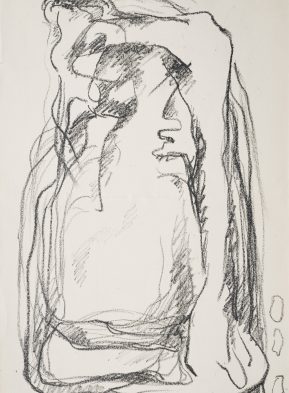

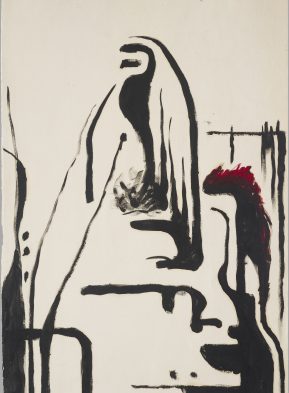

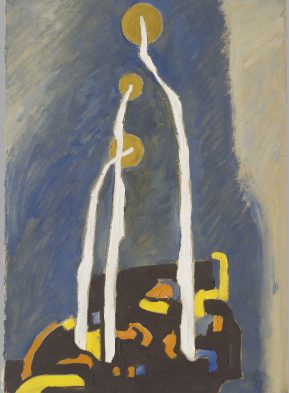

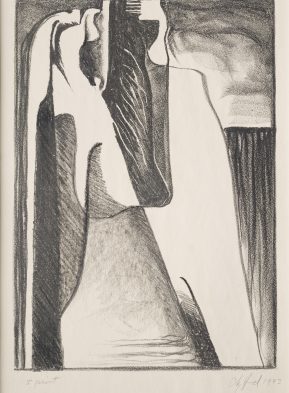

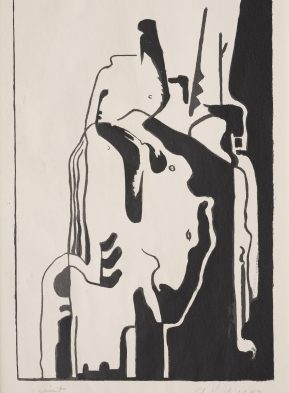

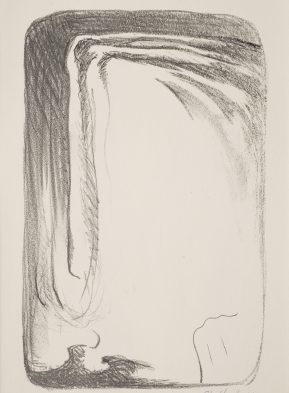

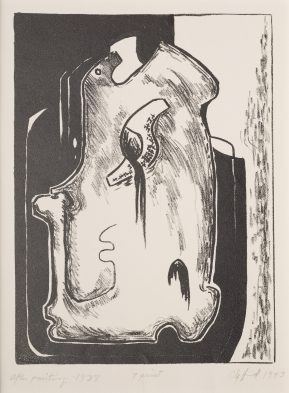

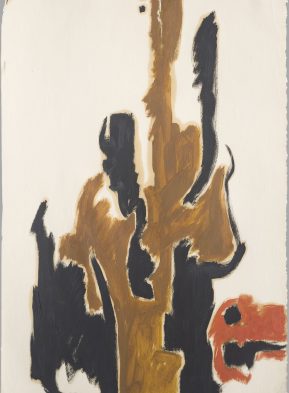

The late 1930s and early 1940s was a fascinating period for Still’s practice, as his output swung between the poles of representation and abstraction. The works on paper from this time were part of Still’s reinterpretation of his own artistic approach and of representational art as a whole. In virtually all cases, they feature upright, slender shapes that replace his earlier work’s images of people, architecture, and machines. Now reduced to compelling contours and other linear forms, their presence is intensified through the pictorial qualities inherent to his oil, pastel, pen-and-ink, and graphite media.

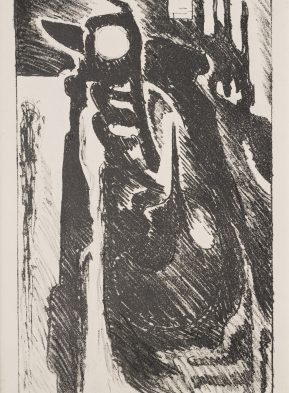

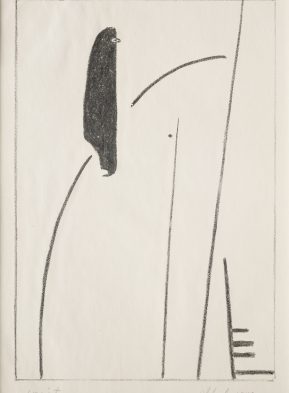

Fine Art Prints

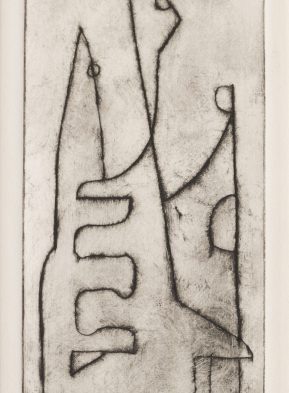

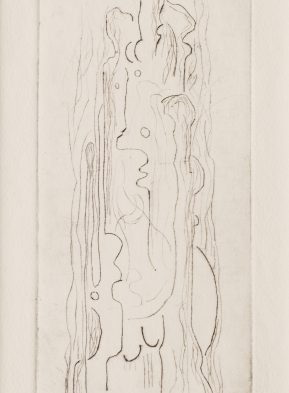

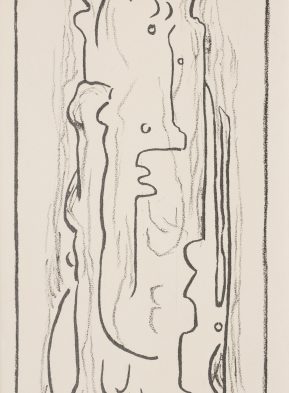

This period is also marked by the occurrence of Still’s only fine art prints, executed in lithography, etching, woodcut, and silkscreen—nearly the full array of printmaking techniques. They foreshadow the flattened space and otherworldliness of his signature Abstract Expressionist works of the later 1940s.

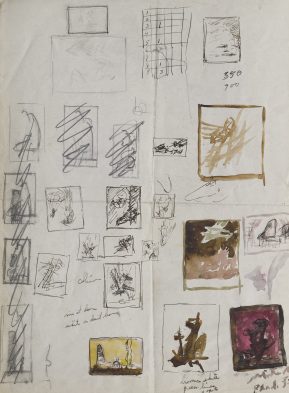

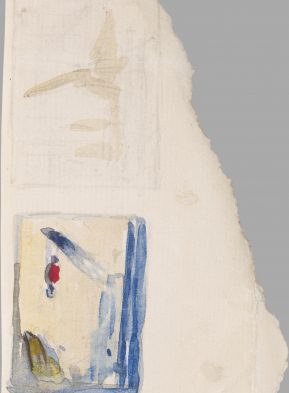

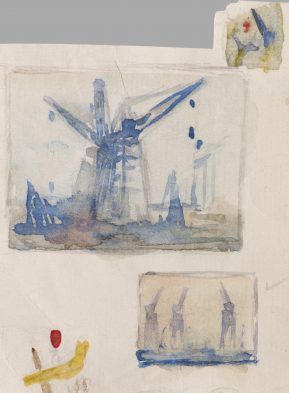

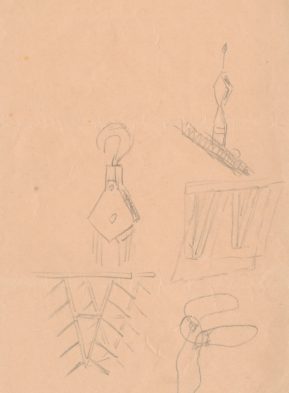

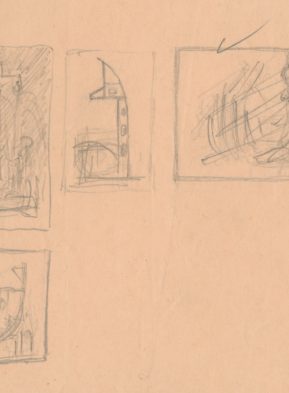

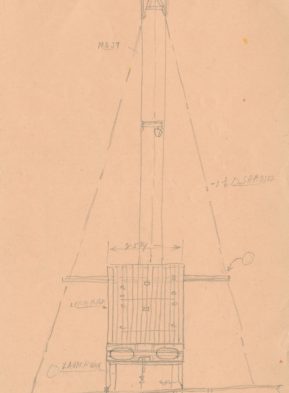

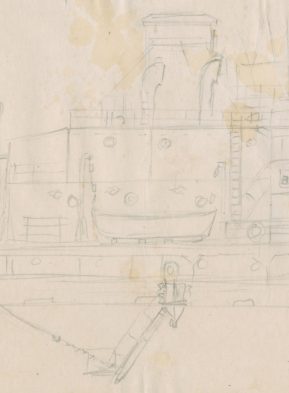

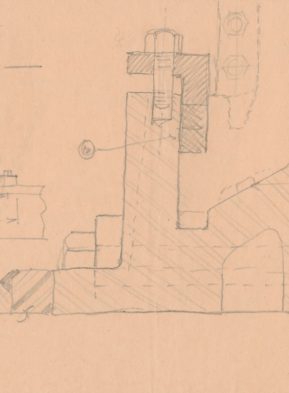

San Francisco Shipbuilding Sketches

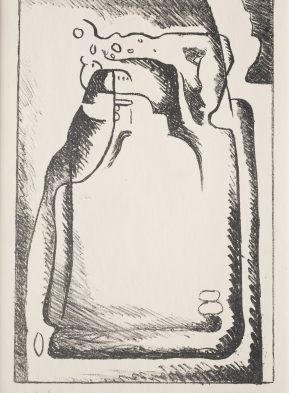

In 1941, when the United States entered World War II, Still relocated to the San Francisco Bay Area. There, he worked in shipbuilding and aircraft construction for the war. These sketches feature the cranes, pulleys, and mechanical devices Still saw at work. He regarded these studies as a type of visual notetaking. They range from highly representational watercolors and blueprintlike studies to more cryptic small sketches in graphite.

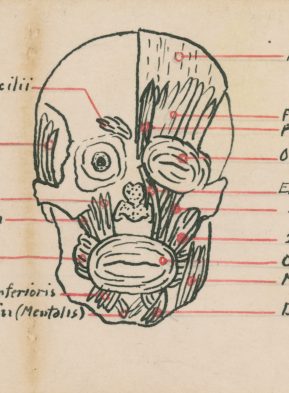

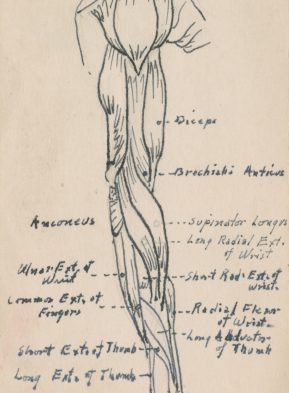

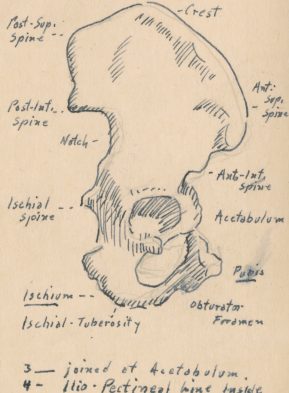

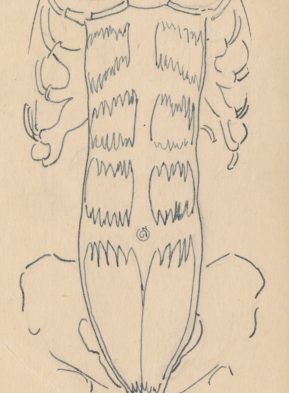

Anatomy Sketches

Still’s burgeoning abstraction was based in perception, drawing, and draftsmanship. From his earliest years, Still observed life around him, pursuing the study of human anatomy during his formal art training. He progressively reduced these figurative images into cryptic symbols: lines, outlines, volumes, and planes.

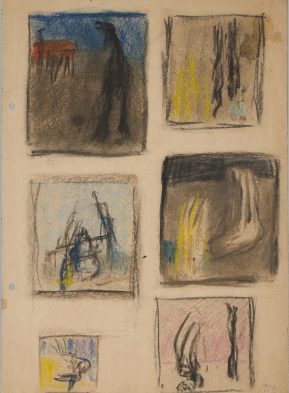

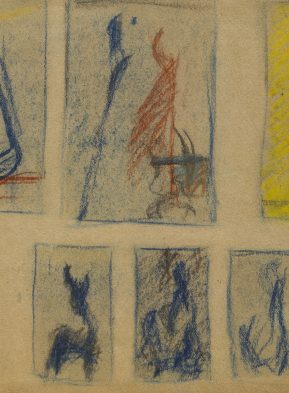

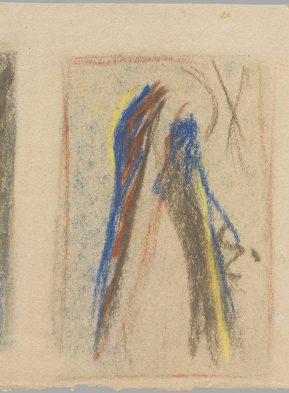

"Notes"

The small “notes” (as Still called them) presented here reveal very early examples of the artist mapping, in microcosm, abstract compositions that test various arrangements of color, surface, line, and shape.

Drawing/Painting/Process

It was common for Still to revisit pictorial ideas from his past, lending them new life. In these two examples, the compositions have been transposed across media, each relying on the inherent properties of their respective media and techniques to determine their ultimate makeup. For example, the forms in PH-536 are more tightly composed than those in PP-128, a parallel pastel work with a lighter, more ethereal presence accentuated by the medium’s powdery nature.

Citation Information

Chicago

David Anfam, Bailey H. Placzek, Dean Sobel. “First Abstractions.” In Clyfford Still: The Works on Paper. Denver: Clyfford Still Museum Research Center, 2016. /worksonpaper/first-abstractions/.

MLA

Anfam, David, et al. “First Abstractions.” Clyfford Still: The Works on Paper. Denver: Clyfford Still Museum Research Center, 2016. 1 Nov. 2016 </worksonpaper/first-abstractions/>.