Landscape

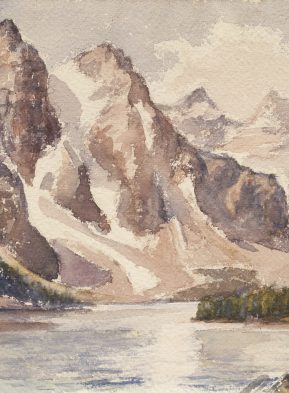

Works made between 1923 and 1936 exemplify Still’s early interest in recording the world around him, especially the landscape, as well as the other most enduring theme in his oeuvre: the figure. Sketches that capture motion—riding, plowing, digging—coexist with studies of grain elevators and other buildings that stress robust structure. Since drawing necessarily involves simplification—three-dimensional volumes become two-dimensional planes and lines—it always entails a certain degree of abstraction. Early on, Still drew inspiration from this aspect of the medium. His pastels and watercolors of the Alberta landscape were strikingly abstract for their time, almost as though the stroke of the brush or the crayon condensed the scenery into an idea rather than an illustration. The pastel stick itself provided a readymade mix of color and linemaking.

From the Renaissance onward, the Old Masters extracted diverse possibilities from draftsmanship. On the one hand, drawings could be quick, realistic studies—made on the spot—which became the basis for more elaborate, highly considered paintings. On the other hand, works on paper were sometimes conceived as fully finished, complex pieces in and of themselves. Still followed this bifurcated lineage. For example, in his graphite sketches of farm labor on the Alberta prairies during the 1920s and ’30s, Still explored both directions: the spontaneous and sensual, and the deliberate and austere. Furthermore, by playing with the two contrasting drawing modes, he overcame the restrictive Renaissance distinction between drawing (disegno) and coloring (colore), instead creating an art in which one dynamic fueled the other.

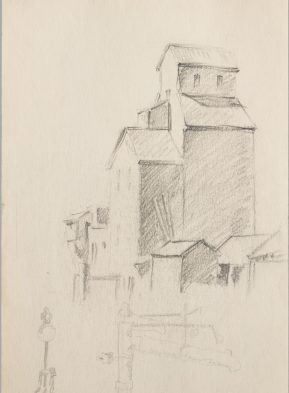

Structures

These architectural structures reflect the angular, faceted style of treating masses that is found in the mature art of Paul Cézanne (about whom Still wrote a master’s thesis in 1935). Their verticality also turns them into stalwart surrogates for the upright human presence.

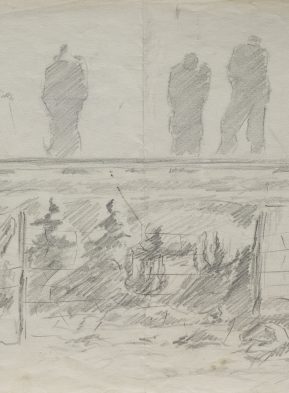

Early Farm/Worker Studies

Drawing requires a rigor and skill that expose a maker’s ability in a way that painting, with its more seductive materiality, can readily disguise. Still’s works on paper— in particular, these graphite studies of Alberta farm workers—show that he was a natural draftsman. In his writings, Still insisted on the importance of the “hand” as an extension of the eye and mind. This idea reveals a philosophical dimension in Still’s practice: it implies that his incisive draftsmanship was the physical embodiment of his innermost sensibilities.

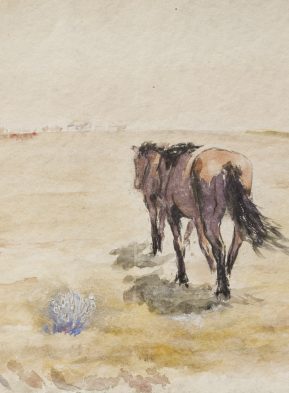

Color Studies

These early pastel and watercolor landscapes depict a central concern with space—conceived alternately as a desolate emptiness or as ethereal fields of color. Significantly, Still later recalled, “[J. M. W.] Turner painted the sea, but to me the prairie was just as grand.”

Citation Information

Chicago

David Anfam, Bailey H. Placzek, Dean Sobel. “Landscape.” In Clyfford Still: The Works on Paper. Denver: Clyfford Still Museum Research Center, 2016. /worksonpaper/the-landscape/.

MLA

Anfam, David, et al. “Landscape.” Clyfford Still: The Works on Paper. Denver: Clyfford Still Museum Research Center, 2016. 1 Nov. 2016 </worksonpaper/the-landscape/>.