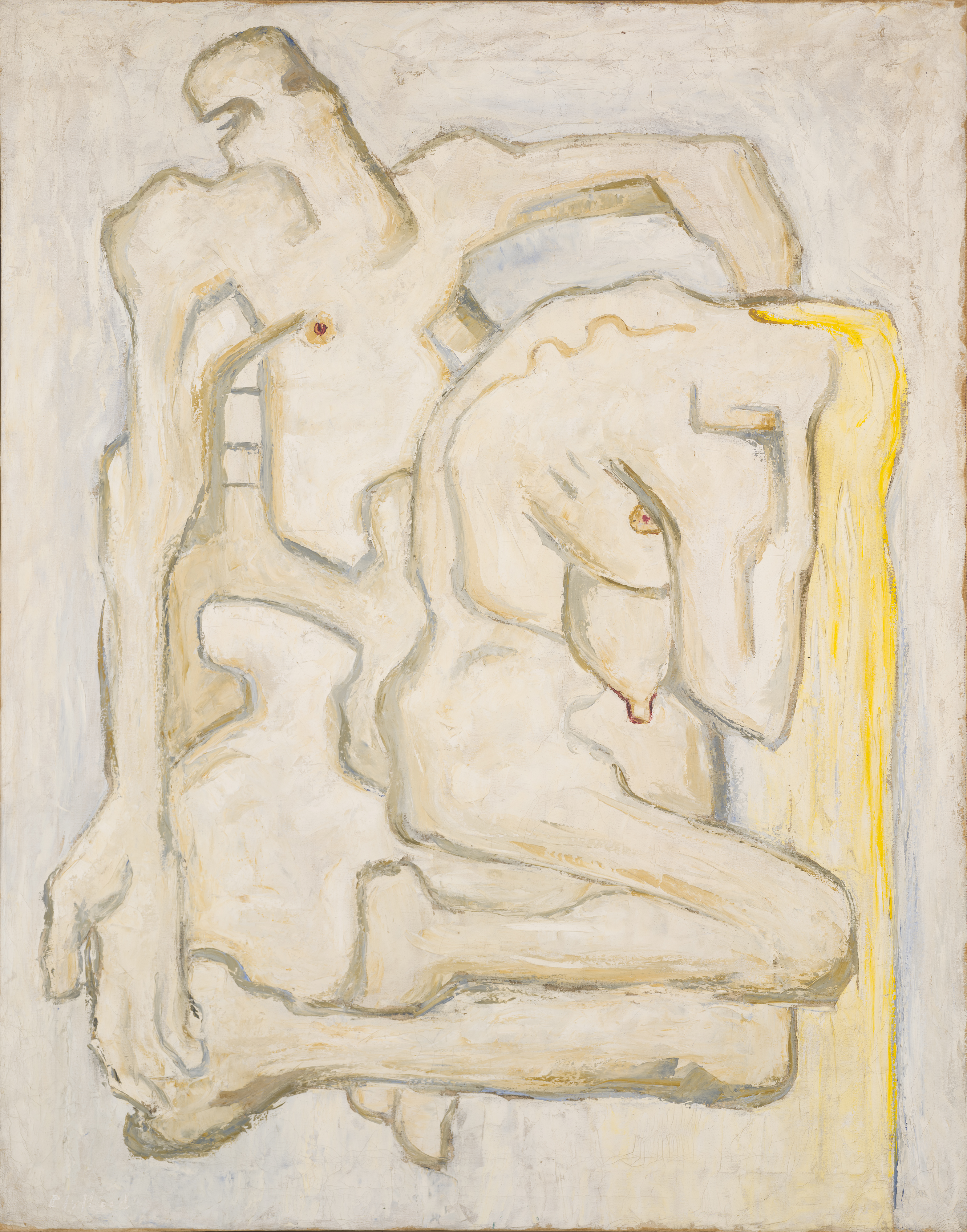

Clyfford Still, PH-469, 1943-44 (detail). Oil on paper, 26 x 20 inches (66 x 50.8 cm). Clyfford Still Museum, Denver, CO. © City and County of Denver / ARS, New York

Rendering the Sublime

By Patricia Failing

Among Clyfford Still’s remarkable accomplishments was his success in setting conditions for the reception of his work. Dealers and museums—even New York’s venerable Metropolitan Museum of Art—bowed to his dictates regarding the display of his paintings and documentation of his career. After his death, more than 90 percent of his lifetime production was sequestered in his personal archive until a museum was established to exhibit the collection according to his explicit specifications.

Still clearly deserved his reputation as a dictatorial outlaw, but the merits of this intransigence were impossible to weigh until his visual archive was made public. The revelation is ironic: it turns out this fiercely private and enigmatic artist was determined to expose the entire ragged arc of his creative journey, including aspirations and practices he expanded, clarified, repeated and left behind. This history manifests itself most legibly in the 2,300 works on paper now in the Clyfford Still Museum collection. Concentrating the evolution of his singular vision from the early 1920s to the 1950s and concluding with a series of pastels from the 1970s, the exhibition illustrates the many frontiers of visual expression Still crossed as he crafted his radical modernism.

Early Development

Still’s youth is routinely pictured as difficult, lonely, and circumscribed by hardship. His parents emigrated from Canada to North Dakota, where Still was born in 1904, and moved to Spokane, Washington in 1905. In 1911 they acquired a homestead near Bow Island, in southern Alberta, where they planned to establish a wheat farm. Droughts, prairie fires, and successive crop failures plagued the region during the teens. By 1920 many farmers were destitute and hundreds of homesteads forsaken. Provincial and federal governments were compelled to mount large-scale relief efforts.1

At age twelve his “life was changed” by reproductions of Titian’s Rape of Europa in Boston’s Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum and Rembrandt’s portrait of his son Titus in the Metropolitan Museum of Art.2 He developed “an intense interest in art,” and, writing of himself in the third person, “spent all the time he could studying the world of color, light, perspective and form around him.” At the same time he “avidly collected books, prints, magazines and acquainted himself with the works of old and new masters until they became familiar. . . . Music and poetry were also studied.”3 In 1915 or 1916, with art supplies provided by his father, Still began to paint.4 He also learned to play compositions by Chopin, Beethoven, and Schubert on the piano.

Although he spent months in Alberta where his parents maintained a house in the village of Bow Island, as well as their homestead a few miles away, Still spent most of his grade-school years in Spokane. By 1909, the population of this exceptionally prosperous city numbered 100,000, and Spokane ranked as the largest US city west of Minneapolis. Before acquiring land in Alberta, Still’s father worked as an accountant in Spokane, and he maintained his business and a modest residence in the city until at least 1917. Still attended the first two years of high school in Bow Island, where he joined a Boy Scout troop his father helped to found, played in the school’s mandolin trio and performed in the Boy Scout orchestra. His natural aptitude for drawing was noted by his peers.5

In 1922, Still returned to Spokane to finish high school, graduating in 1924. He also attended art classes, and was mentored by Spokane University’s dean of fine arts.6 Competent family portraits and Bow Island landscapes from the early 1920s are represented in the exhibition.7 Perhaps at a teacher’s suggestion, in 1923 he acquired his own copy of critic John Ruskin’s 1857 The Elements of Drawing: In Three Letters to Beginners.8 It seems clear that Ruskin’s writings influenced Still’s graphic production and encouraged his lifelong admiration for the work of J.M.W. Turner.

The Elements of Drawing offers a series of exercises and examples for a beginner with an interest in portraying the natural world.9 Ruskin cautions that, even after close and careful observation, nature will always be incomprehensible and mysterious, for it is impossible for the human mind to perceive nature in all of its scope and detail,

Try to draw a bank of grass with all its blades; or a bush, with all its leaves: and then you will soon begin to understand under what universal law of obscurity we live, and perceive that all distinct drawing must be bad drawing and that nothing can be right, till it is unintelligible. [Ruskin’s emphasis]10

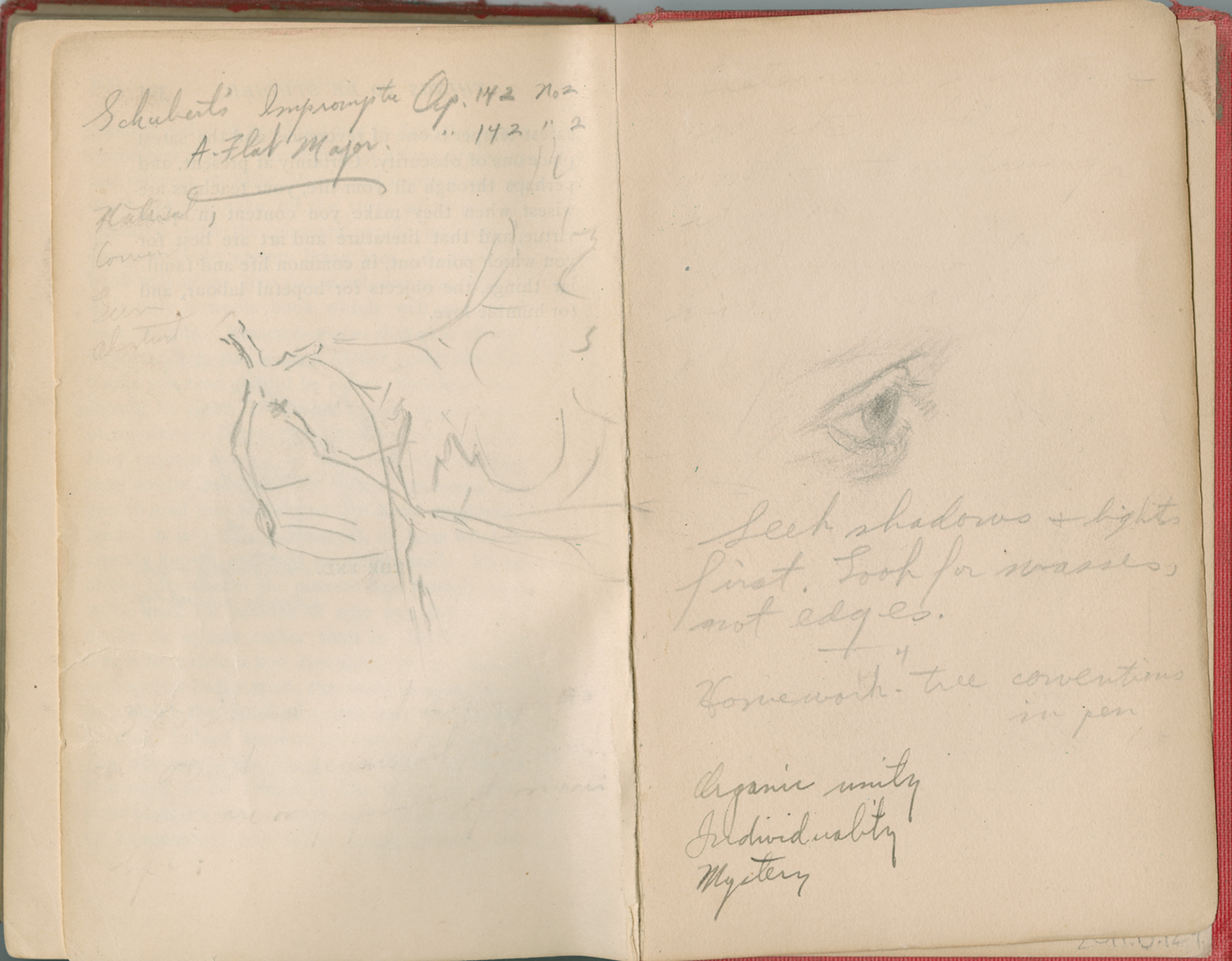

Three laws govern all good landscape drawing, Ruskin advises: organic unity; the individuality of the elements subjected to laws of unity, and the law of mystery—“the law that nothing is ever seen perfectly, but only by fragments under various conditions of obscurity…. Expression of this final character in landscape,” he admits, “has never been completely reached by any except Turner.”11

Still lists Ruskin’s three laws in handwritten notes on his copy of Elements of Drawing, along with other specific Ruskin mandates: “Seek shadows and light first; Look for masses, not edges.”

As Ruskin explains, “A good artist habitually sees masses, not edges, and can in every case make his drawing more expressive by rapid shade rather than contours.”12

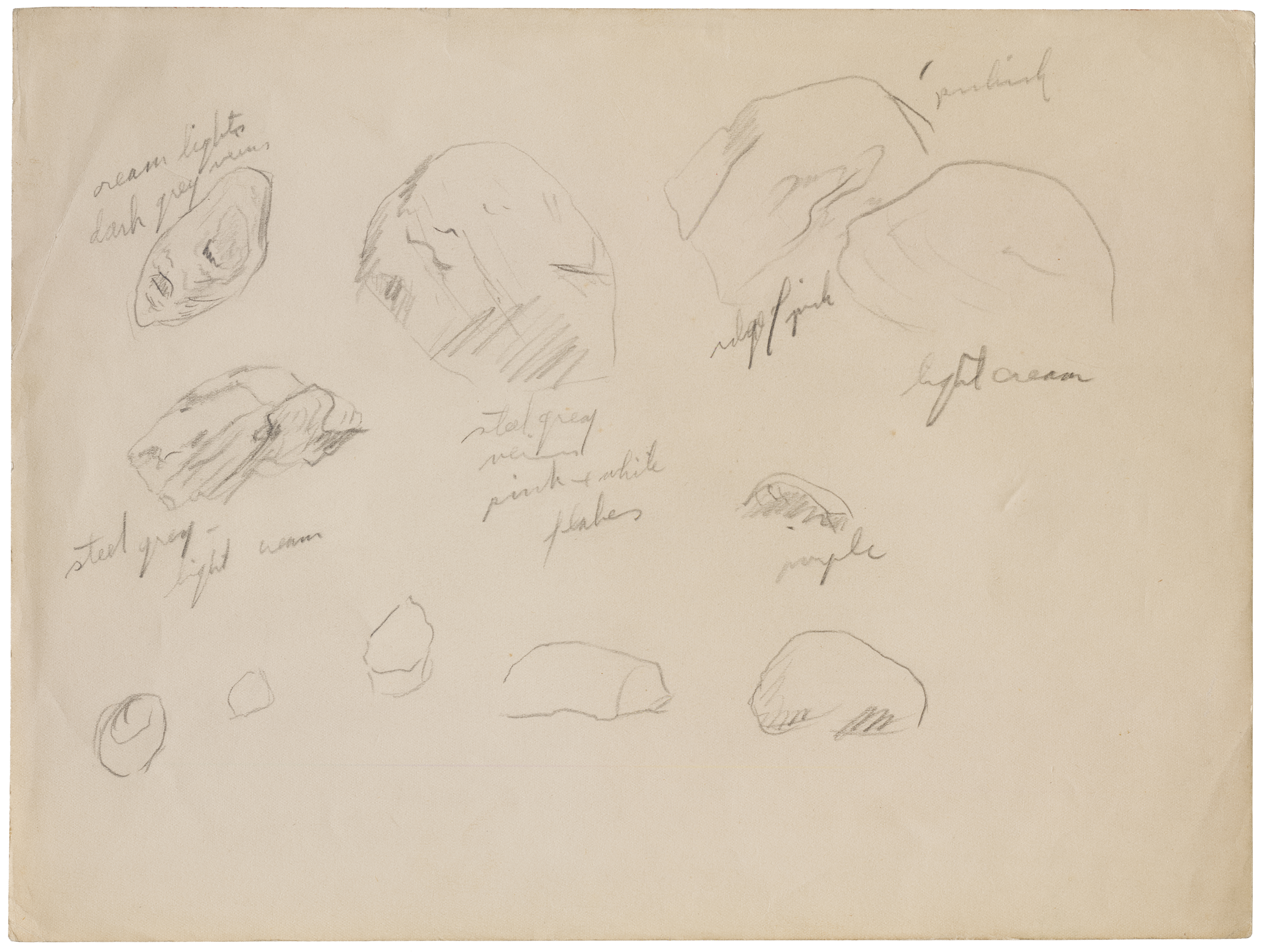

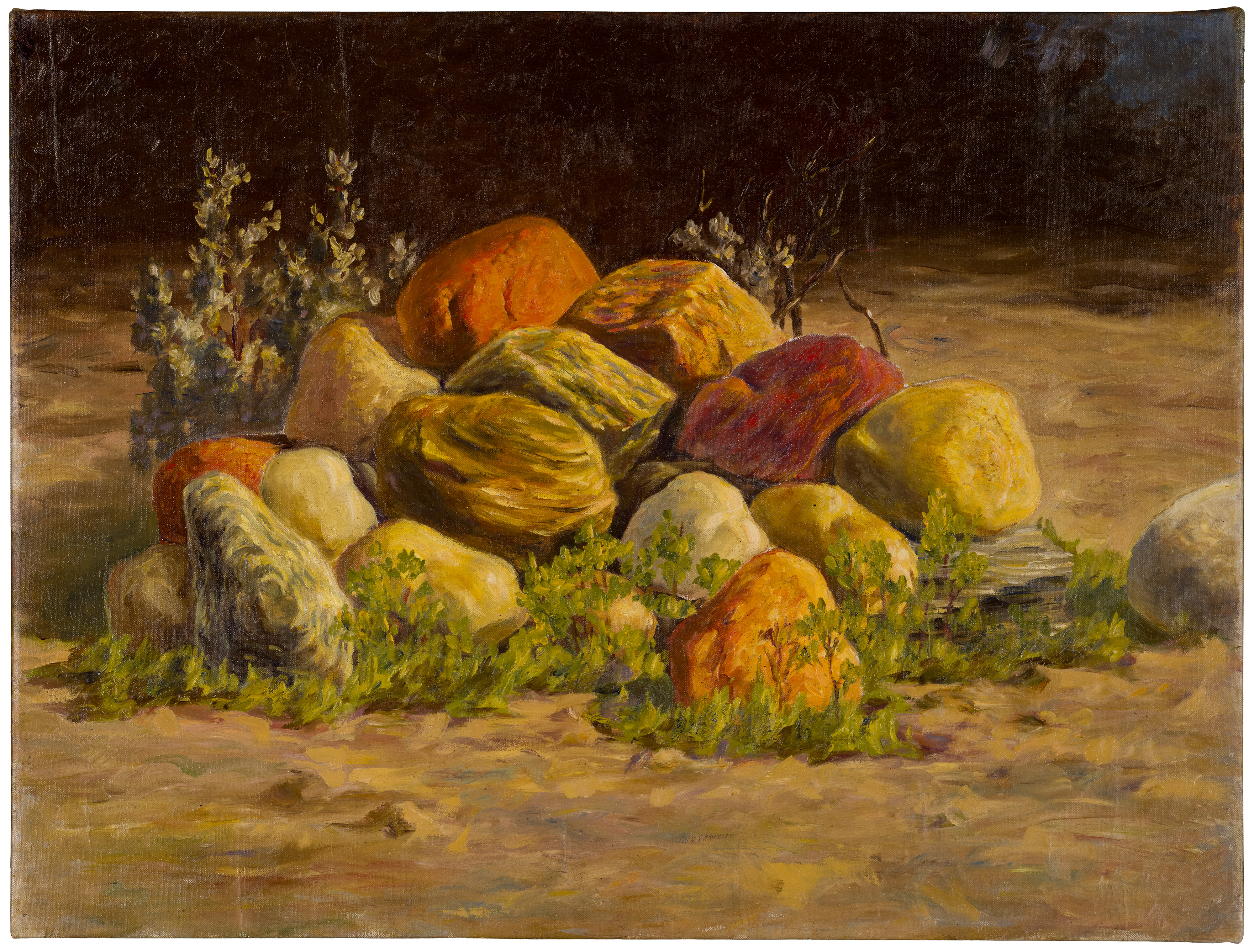

To learn the basics of chiaroscuro, Ruskin recommends drawing a stone illuminated from one side by ordinary daylight. “If you can draw that stone rightly,” he argues,

you can draw anything draw-able…. Drawing depends on your power of representing Roundness . . . for Nature is made up of roundnesses: not the roundness of perfect globes, but variously curved surfaces.13 . . . When you have done the best you can to get the general form [of the stone], proceed to finish by imitating the texture and all the cracks and stains of the stone as closely as you can. . . . A crack must always have its own complete system of light and shade, however small in scale. It is in reality a little ravine.14

The stone exercise is a prerequisite for rendering other landscape features, Ruskin continues,

Draw a piece of rounded rock, with its variegated lichens, quite rightly, getting its complete roundings and all the patterns of the lichens in true local color. Till you can do this, it is of no use your thinking of sketching among hills, but once you have done this, the forms of distant hills will be comparatively easy.15

Still’s undated pencil sketch of stones with notes indicating various nuances of color, PDX-90, conforms to Ruskin’s exercise. The sketch can be related to a 1925 oil painting depicting a stack of field rocks edged with small, painterly masses of vegetation, with almost every leaf a tiny arena for flickers of light and shade.16

Still may have also taken Ruskin’s advice about “color memoranda” in several landscape pastels and watercolors from the 1920s.17 Ruskin suggests the following strategy to execute a successful color landscape sketch:

Give up all form rather than the slightest part of the color . . . never mind that your clouds are mere blots, and your trees mere knobs…. If you want the form of the subject, draw it in black and white. If you want its color, take its color and be sure you have it [Ruskin’s emphasis] . . . [Make] a careful drawing of the subject first, and then a colored memorandum separately, as shapeless as you like but faithful in hue, and entirely minding its own business. This principle, however, bears chiefly on large and distant subjects.18

Whether Still made “careful drawings” of his subjects first or not, his early Bow Island semiabstract landscape pastels correspond with Ruskin’s instructions for making color studies that “mind their own business.” All good landscape drawings, even the most detailed, will always be abstractions of natural facts, Ruskin emphasizes. Furthermore, these abstractions can become a projection of the artist’s own being or soul, provided he dismisses, as much as possible, the visual conventions we use to grasp nature conceptually. If true to the artist’s subjective experience and unrestrained by preconceived ideas, appearances may be transfigured as acts of imagination, the source of all great art.19

Although Still’s annotations indicate that he paid close attention to Ruskin’s Elements of Drawing, his own investigations and instruction from his other teachers undoubtedly aided his progress as well. In the fall of 1925, perhaps as a graduation or twenty-first birthday present, Still’s family supported his travel to New York City “to visit the Metropolitan Museum and see first hand [sic] the paintings I learned to love through my study of their reproductions.”20 He visited major museums and galleries and enrolled in the Art Students League, but dropped out, disappointed by the level of instruction. During his sojourn, he also produced several Turneresque pastel sketches of New York city’s commercial infrastructure—tall buildings, delivery trucks and wagons, ships, the Brooklyn Bridge—rendered in “various conditions of obscurity,” to use Ruskin’s phrase.21 Like Turner’s later drawings, these pastels are hybrids of direct observation and a degree of poetic contemplation. Several Canadian landscapes Still executed after his parents moved north to Killam, Alberta, in 1925, such as PW-3 (1930), belong to a similar category of moody recordings.

Still enrolled as a freshman at Spokane University for the academic year 1926–27, and returned to Canada to work on his parents’ farm after the spring term. Corresponding with a friend in Spokane, he complained about college and farm work and announced that he planned to “throw himself into Art—painting to be specific. . . . Two years I intend to do this—thence to Chicago to study a definite course at the Art Institute of Chicago or under a master, if one will allow me.”22 In 1928, Still decided instead to return to New York and the Art Students League, where he studied with cosmopolitan modernist Vaclav Vytlacil during the winters of 1928 and 1929. He apparently supported himself, at least in part, as a commercial artist, though no visual records of his late 1920s work in New York survive.23 He also worked as a commercial artist for department stores in Spokane, and a pen-and-ink fashion drawing, PDX-128, is a probable vestige of this employment.

In 1931, Still returned to Spokane University after his marriage to Lillian Battan, the daughter of family friends. He played catcher for the university baseball team, served as class president his senior year, and designed the senior yearbook. His drawings during this period include graphite figure studies illustrating farm labor,24 as well as watercolors representing railroads and Alberta grain silos positioned like obelisks against broad stretches of sky. The labor drawings are primarily about movement: wind blowing a horse’s tail; generic male figures lifting, digging and bending; horses pushing forward out of the frame. Unlike the silo and railroad drawings, which correspond to similar compositions in Still’s contemporary oil paintings, the labor sketches were apparently created primarily to hone his skills as a draftsman and observer. Only one extant painting from the late 1920s and early 1930s, PH-419 (1929), corresponds in subject matter to the labor drawings, depicting workers vigorously pitching bundles of wheat into a wagon.25

Aside from portraits,26 human figures are almost entirely absent from Still’s extant oil paintings until 1934, except as compositional accessories.27

Academia

After graduating from Spokane University with a BA in Public School Art and a minor in English in 1933, Still was accepted as a graduate student in fine arts at Washington State College in Pullman (now Washington State University) and awarded a teaching fellowship. He received his MA in 1935 and remained as a member of the WSC faculty until 1941. Nude figure studies of his wife from 1933 verify his command of academic figure drawing, especially the “roundness” of the body, using Ruskin’s term.28

During his tenure at WSC, Still was primarily a drawing instructor. His classes included beginning and advanced semester courses in drawing from casts and costumed models, drawing the human head and figure and freehand drawing. Mediums utilized in these classes included charcoal, colored chalk, pencil, crayon, and wash. He also taught Design (rechristened “Art Structure” in 1938), a class devoted to “fundamental elements and principles of theoretical design and their various fields of work and critical evaluation of pattern arrangements. Attention to the development of taste and judgment in all creative work.” Second semester: “Values of light and dark, color theory, creative color composition: practical problems in all applied arts.” Later in his career at WSC, Still also taught mural painting (the only painting class he taught there), art appreciation, and art history.29

Still archived his teaching notes for his figure-drawing classes. They show he advised students to:

Draw from the model, professional if possible, then mirror. Study structure and form. Avoid sameness in poses. Build up both sides of the figure simultaneously. Care in hands and feet, feet firm on the ground. Do not draw clothes on figures until the figure is correct. Do not hang clothes on the body as a dummy. Give imagination reins, but control. Be patient. Take time.30

In 1936, Still was offered an unexpected opportunity to exercise his skills in portraiture and observational drawing. Worth Griffin, his department chair, invited his junior colleague to join him on a summer expedition to paint Native Americans in Northwest tribes. They visited reservations in Idaho and Montana, but did most of their drawing and painting on the Colville Reservation in northeastern Washington State.31 During their travels, Still produced scores of landscape and portrait drawings of native subjects in pencil, pastels, and crayon, most of them during his stay on the Colville Reservation. Still’s sympathetic portraits are among his most skillful recordings of individual physiognomies, and his sketches of reservation farms and dwellings are unique historical documents.32

Still’s drawings of architecture in the later 1920s and 1930s can be divided into two rough categories: corporate structures rendered as vertical towers with relatively crisp outlines, and sketchy vernacular buildings with sagging roofs, weathered paint, and tacked-on additions.33 Two 1936 images of the same dwelling on the Colville Reservation, one executed by Griffin and the other by Still (PD-101), suggest Still’s lingering debt to Ruskin for drawings in the latter category.

In Elements of Drawing, Ruskin explains that among his initial exercises are drawings of foliage; first, because foliage is accessible, and second, because

its modes of growth present simple examples of the importance of leading or governing lines. It is by seizing these leading lines [that we can give] a kind of vital truth to the rendering of every natural form. I call it vital truth, because these chief lines and are always expressive of the past history and present action of a thing. . . . In a tree, they show what kind of fortune it has had to endure from its childhood; how troublesome trees have come in its way and pushed it aside and tried to strangle or starve it; where and when trees have sheltered it, what winds torment it the most. . . . Try always, whenever you look at a form, to see the lines in it which have had the power over its past fate and will have the power over its futurity. These are its awful lines [Ruskin’s emphasis]; see that you seize on those, whatever else you miss. . . . Now although lines indicative of action are not always quite so manifest in other things as in trees, a little attention will soon enable you to see that there are such lines in everything. In an old house roof, [one observer] will see and draw the spotty irregularity of tiles and slates all over; but a [Ruskinian] draftsman will see all the bends under the timbers, where they are the weakest and the weight is telling on them most, and the tracks of the run of water in time of rain…and he will be careful, however few slates he draws, to mark the way they bend toward those hollows, which have the future fate of the roof in them.34

The Griffin and Still images of the dwelling are rendered from the same angle. Irregular surfaces are expertly recorded in Griffin’s watercolor; clean, legible triangles define the sides of the roof and the surface and shape of each teepee pole leaning against the side of the house are carefully articulated. In Still’s more energetic pencil drawing, lines not only define the dwelling’s form, but also acknowledge vital forces at work in the past and future of this decaying structure. For Ruskin, “awful” lines, action lines, are about understanding the way things are going, about fateful struggles that can expand the meaning of a good drawing. It’s doubtful Still had Ruskin specifically in mind when he drew this dilapidated building, but there may be an echo here of Ruskin’s argument that certain kinds of line can embody vital truths.

Among Still’s reservation drawings is a street scene executed in pencil, PD-94 (1936). This preparatory drawing maps out the composition of a subsequent oil painting in detail, and is rare in Still’s oeuvre. Painter Sidney Dickinson, who met Still at WSC in 1934, described the artist’s typical working method in a letter to a colleague, reporting that Still “has a positive passion for this region of which he is native and already shows signs of going to the very top as an exponent of the American scene as it exists in Western rural life. . . . He is most engaging, lean and gaunt and burning up with the urge to paint. He works from hundreds of notes and sketches.”35

With Dickinson’s support, Still spent the summer of 1934 at Yaddo, the venerable artists’ retreat in Saratoga Springs, New York, and returned again in 1935. For the rest of his life Still regarded his Yaddo summers as “among the very important moments in the development of my life’s work . . . the beginning of moving away from painting as reacting to what one sees from outside to [a] concept of painting as inner comprehension.”36 As his approach to painting shifted toward imaginative expression, the human figure moved from the realm of drawing and into his oil-on-canvas production.37 The Clyfford Still Museum collection includes nineteen small paintings created at Yaddo. Most are ominous scenes foregrounding a single male or female figure. In 1934 and 1935, Still also began a series of oil paintings in Pullman that he characterized as a “turn away from landscape to the figure, dealing with the figure imaginatively, and with a kind of austerity.”38 In these canvases, emaciated rural men and women with huge hands and feet and elongated mask-heads are posed in nightmarish tableaux. Figures will appear again in his works on paper of the early 1940s, reimagined as fragmented signs of vital presence.

San Francisco, Richmond, and New York

In 1941, Still resigned his position at WSC and moved with his family, which now included his daughter Diane, to the San Francisco Bay Area. He found employment in war industries, as a steel checker for Navy shipyards, and then as a materials release engineer for Hammond Aircraft.39 He also worked as a crane operator. Time to pursue painting was limited, but he managed to complete several rather astounding canvases between fall 1941 and fall 1943, when his aircraft contracts were completed. These paintings range from representational scenes of shipyard labor to abstractions riffing on the shapes of tools and construction equipment to spare calligraphic compositions reminiscent of Joan Miró. His drawings, all abstractions, are also unpredictably diverse: in PH-550 (1942)—probably a preparatory study for the painting PH-757 (1942)—three white stalks crowned with golden discs crank skyward from a mysterious foundation; PH-457 reads as a goofy mechanical toy equipped with both insect and human anatomy. PH-530 could be a reverse X-ray of some unknown and unknowable organic being.

The Richmond Professional Institute (then a division of the College of William and Mary) in Richmond, Virginia, hired Still as an instructor in the fall of 1943. He taught mural painting, sculpture, anatomy, printmaking, painting, and—again—drawing. After reorganizing the school’s lithography facilities, Still executed a series of twenty-one lithographs. The group includes images replicated from earlier paintings, variants of his current paintings and drawings, and independent explorations with lithographic crayons.40 The reworkings of related paintings are relatively easy to identify and sometimes reveal new information about companion oils. The print PL-8 (1943), for example, suggests contours and clarifies shapes obscured by the painterly brushstrokes in PH-156, a corresponding oil painting from the same year. The other two categories are difficult to delineate, since most of the lithographs incorporate formal motifs or strategies that appear, directly or indirectly, in other contemporary drawings or paintings.41 In most of these prints, however, dominant forms are clustered in the center of the composition and figure-ground relationships are clearly legible. In this respect, they lag behind Still’s exuberant 1943 and 1944 oil-on-paper compositions, the harbingers of his most original artistic achievements.

Although Still complained about “the burden of a tremendous load of classes” (thirty-two weekly contact hours),42 his tenure at Richmond had certain affinities with his more luxurious summers at Yaddo. Distanced from the West Coast and his former academic colleagues, working alone with no professional demands other than teaching, he rapidly transformed his visual resources into unprecedented creative instruments. The process involved revisiting, editing, and reconfiguring animated linear gestures, silhouettes, and blazing shapes, moving backward and forward in the repertoire of his production simultaneously. As Still explained, “I did not make new shapes in order to be original. They grew out of what I was doing.”43 In the late 1930s, his abstractions struggled with the weight of “what one sees outside.” In Richmond, the weight is lifted, although representational forms reappeared in his work from time to time throughout his career.44

A composition repeated in Still’s Washington State oeuvre conjoins male and female nudes with interlocking bones: Adams and blonde Eves. In an early example from 1936,45 the male figure makes an apparently protective gesture toward the faceless female, who hunches over as if weeping.

In 1938 and 1939, a glowing orb, a sign of growth and regeneration, accompanies the intertwined couples, perhaps an autobiographical reference to Still’s new status as a father. These images belong to a series of renderings alluding to cosmic dualisms: nature/culture, earth/sky, flesh/spirit. Still began reading Friedrich Nietzsche in high school, and Nietzsche’s account of eternal clashes between rationality and instinct, and structure and chaos, echoes in Still’s efforts to reinvent his artmaking as a pure instrument of thought.

Still returns to images of intertwined couples as late as 1944 in PH-93, depicting a male figure supporting a collapsing female.46 Blood flows from her hip, or perhaps from his. In other Richmond works on paper, the two figures dissolve into animated vertical fragments. The fragments tend to be ordered in centralized groupings in which figure and ground are integrated internally, although foreground and background can still be identified in the overall composition. The same foreground/background dynamic holds for simplified ideograms: in PH-482 (1943), for example, Still condenses a recollection of wheat-farm summers into three lines of yellow paint and a red circle over a white background. Wriggling linear biomorphs in PH-493 (1943), a variant of PH-514 executed three years earlier, are also imposed on a white background space.47 Other examples, however, complicate these distinctions. The lower-right corner of PH-483 (1943), a schematic allusion to a bony shoulder, ribcage, and hand, integrates figure and ground, and in PH-507 and PH-508 (both 1943), figure and ground become interchangeable. In PH-536 (1943), ragged, upward-thrusting forms are again superimposed on a white background, a format left behind in a 1944–45 painting of the same forms developed as an integrated field. In another variant of this composition in pastel, PP-128 (1952), the field effect is realized simply by opening up the air between softer ochre, red, and black shapes and by lateral red and black projections suggesting expansion beyond both sides of the picture plane.

Graphic calligraphy executed with a brush appears in many of the Richmond works on paper, but Still also explored a range of surface effects created with a palette knife. Distinctions between drawing and painting are murky at this point; most of Still’s Richmond “drawings” were executed in oil paint on paper, albeit on a smaller scale (about 13” x 20”) than his fully developed oils on canvas. Graphic effects in palette-knife compositions PH-525 (1943) and PH-489 (1944) range from relatively delicate marks to thick, blunt inscriptions. These drawings in particular anticipate Still’s crusty canvases of the later 1940s, not only in their surfaces, but also in the intimacy of their figures and ground. As Clyfford Still Museum senior consulting curator David Anfam has observed, “Still was capable of extremely meticulous draftsmanship rendered, unusually, with a palette knife.” The “drawing” in his mature paintings “lies in Still’s supreme command of how to handle edges. Still crafted the peripheries of his shapes with an unerring precision—it is these contours that bring the fields of color to life, making them bite into the space of the canvases.”48

There are hints of Picasso and Miró in some of the Richmond drawings, but the collective effort of more than two hundred works on paper can be summarized as a quest for a unique manner of expression. His ambition, Still explained, was to achieve “a fusing of space and form into a total energy,” in part by circumventing what he regarded as a Bauhaus compositional practice of adding unit to unit, ordered in hierarchies.49 Also integral to his emerging inner vision was an expanded repertoire of vertical shapes and lines—“life lines”—expressive of spirit, freedom, growth, defiance of gravity, aspiration, and upright human beings. With these visual signals, Still hoped to engage “the sublime in man, that which is significant and great in man’s spirit, not the magnitude of the world outside him.”50

Still moved to New York in the fall of 1945, accompanied by several large-scale paintings executed in Richmond. The largest (105” x 91 ½”), PH-235 (1944), nicknamed “Red Flash on a Black Field” and inspired by a Richmond drawing,51 has been nominated by several historians as the first Abstract Expressionist painting. Still explained that, although each of his Richmond oils on paper was a complete work of art and not a preliminary sketch for a large one, “in a few instances I found that the idea demanded a larger field.”52

In 1946, Still returned to San Francisco to teach at the California School of Fine Arts (now the San Francisco Art Institute), where he remained on the faculty until 1950. By 1947, he was in full command of technical and conceptual strategies that impressed artists such as Jackson Pollock and Robert Motherwell when his paintings were shown in New York. In these expansive canvases, with crude, scruffy surfaces evoking blood, earth, soot, ghosts, and thunderclouds, figuration was entirely absent, yet lurking, somehow, in the paintings’ verticality, palette, and chromatic interactions. Space was no longer defined by line: with carefully designed interpolations of color and shape, surfaces as tangible as a wall expanded into infinity. A preface to these accomplishments was certainly Still’s long experience teaching color theory and design, also manifest in the visual rehearsals he continued to carry out in oil, gouache, tempera, and watercolor compositions on paper.

In late ’40s and early ’50s drawings, Still took breathers, in effect, from the grandiloquent dramaturgy of his large-scale canvases. In a 1950 series executed with a palette knife, PH-465, 466, and 467, surfaces are as feathery and muscular as in his big pictures, but here only a few compact color shapes interact within environments of white. Even in earlier compositions such as PH-510 (1946), two solitary red and black rockets of color fly upward into white ether.53 The white field of PH-556 (1949) is occupied only by a faint gray streak and a long yellow line on the right margin. This kind of minimalism, together with the animated drawing strokes of early ’50s pastels, comes around again in late canvases such as PH-1049 (1977), where small fragments of color explode on a huge white canvas.

Although Still railed mightily against the shortcomings of art schools, after he left San Francisco and moved back to New York in 1950, he offered courses in graphic techniques at Brooklyn College in 1952 and 1953. In his studio, he continued a series of pastels begun on the West Coast. Resurfacing in these pastels are conflagrations of color recalling the Native American blankets and shawls in Still’s 1936 reservation drawings. In other pastels, Still transfigures his misty blue, pink, and pale green Bow Island color memoranda into elongated sheets of textured color, like frost on a window. Other examples, such as PP-136 (1957), return in form and color as full-scale paintings decades later.

Still recycled a unique set of images in the 1968 pastels he titled Memories. These drawings are nostalgic representations of farm scenes copied from notes and drawings dating from the late 1920s. The Memories pastels have been cited as examples of Still’s dialectical shifts among present, past, and future, but they also relate to his family history. Still’s father died at the age of ninety in 1968. Although Still made few statements on the record about his parents, he did report that his father “never approved of him.” Other acquaintances remember the family as dysfunctional. Still’s father, John Elmer Still, was a dedicated Christian, and their correspondence documents Still’s resentment of his father’s judgments. “Your letters imply that I live in some sort of sin; that my soul is guilty,” Still writes in a 1953 letter. “You have an uncanny way of sensing when I might have backed in a wall in a fight and adding that nasty ‘it doesn’t pay’ when it hurts the most. This is a reminder that I want no more of it. . . . As I have said before, your prayers are welcome, but don’t forget yourself. The Devil has many tricks to deceive.”54

Other letters from Still to his father from the 1950s are gracious and routine: “I received your gloves a few days ago. They are excellent and warm. I wear them every day. Thanks again.” Still’s father replied with detailed reports about the Alberta farm and his mother’s deteriorating health. After she died in 1960, Still invited his father to stay with him in New York, signing the invitation “Love, Clyfford.” His father remained in Canada, and father and son continued to correspond on friendly terms until his father died. Still undoubtedly associated his father with the hard labor and calamities of dry-prairie farming; as a young man, however, he had written approvingly of the family farm as providing “inspiration while I’m painting and nourishment when I’m not.”55 Still’s Memories pastels can easily be read as dreamy recollections of youthful inspiration, but they may also, perhaps, represent an indirect homage to a difficult and distant father.

Still left New York in 1961 and moved to rural Maryland, where he lived and worked until he died in 1980. In his last decade he created over a thousand pastels. Beginning in the mid-1970s, they serve as a visual diary, documented by month and day. Most are exuberantly calligraphic drawings on colored paper that barely contains ethereal whirling, surging and exploding tracks and masses of color. As is typical in relationships between his later drawings and paintings, the creative inbreeding between these pastels and concurrent canvases is realized through a process of extending, clarifying, and realigning colors, marks and spaces—intimacy and distance at the same time.

Clyfford Still’s Drawings and Abstract Expressionism

Debate about Still’s standing as an Abstract Expressionist has often pivoted around the orthodoxy of “action painting,” imagined as an unpremeditated encounter with an empty canvas resulting in unexpected imagery.56 Reviewing the working methodologies of the first-generation painters associated with Abstract Expressionism, none actually conform to this cliché, and certainly not Still’s artistic practices. As Still explained to his friend Betty Freeman, when he began a large canvas, he had the image of an idea fully in mind before he started: execution was just a matter of “letting the images roll.”57 His graphic production, with few exceptions, was founded upon an expanding circle of reflections on his own visual output, not unpremeditated accidents.

A more significant angle of inquiry regarding Still and his status as an Abstract Expressionist implicates the practices of drawing. According to critic Clement Greenberg’s narrow but not irrelevant history of Abstract Expressionism, the story begins in the early 1940s when progressive painters belonging to no movement or school became engaged with certain formal challenges. These included,

loosening up the relatively delimited illusion of shallow depth [adhered to by] the three master Cubists—Picasso, Braque, Léger. . . . If they were to be able to say what they had to say, [the Americans] had also to loosen up that canon of rectilinear and curvilinear regularity in drawing and design which Cubism had imposed on almost all previous abstract art. These problems were not tackled by program. . . . What happened, rather, was that a certain cluster of challenges was encountered, separately yet almost simultaneously, by six or seven painters [Still, Pollock, Hofmann, William Baziotes, Motherwell, and Mark Rothko] who had their first one-man shows at Peggy Guggenheim’s Art of This Century gallery in New York between 1943 and 1946.58

The most radical response to Cubism’s challenge by these artists, Greenberg argues, was “the effort to repudiate value contrast as the basis of pictorial design.” Turner, he concludes, “was the one who made the first significant break with the conventions of light and dark.” Turner achieved this break in his late paintings by narrowing value intervals at the light end of the color scale and by minimizing contours, remanaging drawing to dissolve sculptural effects. By elaborating Turner’s accomplishment, Greenberg argues, “Clyfford Still emerged as one of the original and important painters of our time—and perhaps more original, if not more important, than any other of his generation.”59

Most original or not, Still was clearly not the most influential artist associated with first-generation Abstract Expressionism, even though Greenberg credits him with initiating a two-person “school” of inventive followers, Barnett Newman and Mark Rothko. Drawing played a significant role in Still’s historical dynamic. Willem de Kooning was widely emulated by abstract painters in the United States by the end of the 1950s, in part because he relied upon traditional devices of contour and chiaroscuro to render his female figures. His paint-loaded gestures could also be related to drawing marks and structural ordering. Still’s paintings, in contrast, looked “unformed.” As one of his contemporaries recalled,

those very large, ragged areas seemed intentionally NOT to be drawn. . . . There was no line. No gesture except repeated trowelling of the color and the edges were just the result of paint application. . . . It was a rejection of the kind of drawing which is implicit in the painting of Bill [de Kooning], say, or Franz [Kline] . . . None of the opposition of form, you know, we used to expect in those days.60

Although critic Robert Hughes admired Still’s originality, when comparing him to de Kooning, Hughes also found Still’s drawing “clumsy” and his paint surface “crude.”61

Ironically, draftsmanship was a condition for the execution of Still’s mature paintings. As Greenberg observed, Still “had to accept the torn and wandering [lines] left by his palette knife”62 in structuring his pictorial formations and designing the edges of his shapes. As his painting and drawing archive reveals, Still’s skill, dexterity, and expertise in traditional drawing practices were always at the very heart of his formal innovations, as well as the expressions of meaning in his art.

- See David Jones, Empire of Dust: Settling and Abandoning the Prairie Dry Belt (Edmonton: The University of Alberta Press, 1987). ↩

- The portrait of Titus was subsequently downgraded to “style of Rembrandt” and is no longer on view. ↩

- John O’Neill, ed., Clyfford Still, exh. cat. (New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1979), 177. ↩

- James Demetrion, ed., Clyfford Still: Paintings 1944–1960, exh. cat. (Washington, DC: Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, 2001), 162, 167. ↩

- Fred Mellen, “Famous Artist has Bow Island Roots,” 40 Mile Country Commentator (February 3, 2013), 1. Silver Sage: Bow Island 1900–1920 (Bow Island, Alberta: Lions Club, 1972) records several details about Still family activities in Bow Island. ↩

- Allegra Askman, “Still Life,” Spokane Magazine (June 1980), 21–22. The high school was an adjunct of Spokane University, a local four-year liberal arts college. Maude Sutton, a dean at Spokane University, apparently befriended young Still, advising him, “You have special talent and you owe it to yourself to pursue it.” ↩

- Examples include PD-1 and PD-2 (both 1924), PW-18, PW-9.1, and PP-482 (all 1923). ↩

- Demetrion, 162. Still was apparently already familiar with Mornings in Florence (1875–79), Ruskin’s guide to Christian art and iconography in the city’s churches. The volume was included in the collection of informal lending libraries operated by Bow Island churches. Still’s parents were devout Christians, active in Bow Island’s United Church. Clyfford Still’s personal library in the Clyfford Still Museum Archives includes four volumes of Ruskin’s Modern Painters as well as The Elements of Drawing, inscribed “Clyfford Still 1923.” ↩

- “Nothing is said of figure drawing” writes Ruskin in Elements of Drawing, “because I do not think figures, as chief subjects, can be drawn to any good purpose by an amateur. As accessories to landscape, they can just be drawn on the same principles as anything else.” John Ruskin, The Elements of Drawing; in Three Letters to Beginners (New York: Dover Publications, 1971), 18. Utilizing techniques Ruskin suggested, however, Still executed dexterous pen-and-ink sketches of his parents in 1924 (PD-1 and PD-2). He was already producing convincing portrait heads in oil and pencil in 1923, including his self-portrait at age eighteen, PH 672. ↩

- Ibid., x. ↩

- Ibid., 115–121. Ruskin advises his pupils to learn to draw first with pen and ink to establish contours and basic light-dark shading, moving on to pencil “to tint and gradate tenderly,” and then to brush and watercolor to lay on masses and tints of shade. Still’s 1923 drawing of a cow, fence, and shed with lighting from the left (PD-3) could be used to illustrate Ruskin’s beginning pen-and-ink exercises. ↩

- Ibid., 83. In 1933, Still reversed this logic, replicating the pastel landscape PP-482 (1923) in a pen-and-ink contour drawing, PD-61 (1933). ↩

- Ibid., 49–50. ↩

- Ibid., 54. ↩

- Ibid., 111. ↩

- The painting is PH-45 (1925). Still later cited this composition as among the most significant for tracking his early creative development. He executed PH-130, a similar, more painterly version, in 1926. For Clyfford Still Museum senior consulting curator David Anfam, the paintings represent much more than an exercise. The imagery, Anfam writes, can be related to Jane Ellen Harrison’s Themis: A Study of the Social Origins of Greek Religion (1912). In this text “Still could not have missed the centrality of rock/stone (and blood) as ritual substances in Harrison’s narrative, where they embody the awesome magic of ‘the Earth.’” David Anfam, “Still’s Journey,” Clyfford Still: The Artist’s Museum (New York: Skira Rizzoli Publications, 2012), 87. According to Anfam, Still was “obsessed with stone.” Ruskin may have been the first to call Still’s attention to stones as microcosmic arenas. ↩

- PP-842 (1923), PP-26 and PP-27 (both 1922), and PW-22 (1927), for instance, could be characterized as “color memoranda.” ↩

- Ruskin. Elements, 136. ↩

- Ibid., ix, xii. Ruskin’s views on creative imagination are elaborated in volumes of Modern Painters, which Still also owned. ↩

- Demetrion, 162. ↩

- These pastels include PP-845, PP-846, PP-847, PP-848, PP-849, and PP-850 (all 1925). ↩

- Clyfford Still, letter to Weldon Schimke, 13 August 1927. Clyfford Still Museum Archives. ↩

- Thomas Hart Benton was also an instructor at the Art Students League in 1928 and 1929. Although Still’s 1920s farm paintings have been associated with Benton’s regionalism, Still chose to work with Vytlacil (1892–1984), an acolyte of Hans Hofmann. ↩

- PD-10, PD-11, PD-13, PD-14, and PD-15 (all 1930) are representative examples. ↩

- Oil paintings PH-1001 and PH-616 (both 1929), also represent farm laborers, but the figures are seated or resting. ↩

- Still regarded his portraits as mere “factual records,” never part of his serious work. Clyfford Still, exh. cat. (San Francisco: San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, 1976), 109. ↩

- Aside from PD-419 (1929) and the two canvases listed in note 25, the CSM collection includes only one other pre-1934 oil with a focus on the human figure, PH-784 (ca. 1924), which appears in a photograph of young Still at the easel. This photograph reveals that the painting’s subject was originally a farmer plowing with horses, and was more about the horses than the farmer. The painting was later cut down and the horses eliminated. ↩

- Still also depicted his wife’s torso in a succinct pen-and-ink outline, PD-39 (1933), reminiscent of Matisse’s drawings. Anfam suggests, however, that Still may have modeled his style on the reductive linearity of American cartoonist Al Frueh. ↩

- Several WSC course catalogs with class descriptions from the 1930s and 1940s are posted online at https://research.libraries.wsu.edu/xmlui/handle/2376/5781. Others are housed in Manuscripts and Special Collections, Holland Library, Washington State University, Pullman, Washington. ↩

- State College of Washington teaching notes, Clyfford Still Museum Archives. ↩

- The Colville Reservation was established in 1872. People from twelve different tribal groups were ultimately assigned to the reservation. In 1912–13, the Colville Indian Agency Headquarters was moved to the small town of Nespelem, Washington, a venue for Fourth of July celebrations that included weeklong, intertribal pow-wows attended by native people in new and heirloom regalia. Construction of the Columbia River’s Grand Coulee Dam, which joins reservation land on its east end, began in 1933. Its consequences for reservation culture were severe: no provisions for a fish ladder were made for Grand Coulee, and by 1938, the progress of the dam had stopped all salmon from migrating upriver.

Still and Griffin were headquartered in Nespelem in 1936, and in 1937 established a Washington State Summer Art Colony there. The colony, designed primarily to attract art teachers and advanced students during their summer breaks, continued until 1940. Griffin taught portraiture. Still served as colony instructor in 1937 and 1938, in charge of landscape painting and composition. ↩

- Among Still’s Colville drawings in the exhibition are PP-241, PP-485, PP-486, PP-489, and PP-494 (all 1936). In 2015, the Clyfford Still Museum mounted a broad survey of Still’s reservation drawings and paintings, “Clyfford Still: The Colville Reservation and Beyond, 1934–1939,” and published an exhibition catalogue with the same title. ↩

- There are oil paintings related to the second category as well: PH-423 (1927) for example, represents wooden buildings and sheds with missing side boards and a yard filled with debris. The two categories sometimes merge: in PH-422 (1929), for example, weathered sheds and broken fences coexist with sleek grain silos. ↩

- Ruskin. Elements, 91, 96. ↩

- Sidney Dickinson, letter to Elizabeth Ames, ca. March 1934. Ames correspondence, Box 289, Yaddo Records, The New York Public Library Special Collections. The Clyfford Still Museum Archives includes several genres of Still’s period notes, including drawings with written notations; sketchbook pages with several rectangles containing fragmentary images, rehearsals for future production; cursory outlines for the basic compositional structure of paintings; fully articulated sketches; and color memoranda. Still also occasionally worked from photographs as aides mémoire. ↩

- San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, 108. ↩

- Reflecting on his mature production, Still proclaimed, “The figure stands behind it all.” At its most simplistic, this statement might reference the shift of figurative imagery from observational works on paper to his mid-1930s oil-on-canvas “experiments in the manipulation of the human figure in the interests of interpretive design.” Anfam analyzes the broader implications of Still’s proclamation about the figure in his essay “Clyfford Still’s Art: Between the Quick and the Dead” in Demetrion, 21–28. ↩

- David Anfam, Clyfford Still (London: University of London at the Courtauld Institute of Art, 1984), 50. ↩

- San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, 109. ↩

- Ibid., 110. ↩

- I’m indebted to Clyfford Still Museum assistant curator and collections manager Bailey Placzek for her expertise in tracking relationships between Still’s lithographs and his other past and contemporary paintings and drawings. ↩

- O’Neill, 181. ↩

- Betty Freeman, “Clyfford Still: A Study, 1968,” 86. Betty Freeman Papers, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC. ↩

- Even some of the Richmond drawings include not just vestiges of figuration but straightforward representational imagery: stalks of wheat appear in PH-547 (1943), for example, together with black fragments reminiscent of the head and arms of his mid-1930s mask head figures. ↩

- PH-726 (1936). Other examples of this imagery include PH-434 (1938) and PH-398 (1939). Anfam relates PH-726 to Picasso’s 1903 La Vie. The ominous content of Still’s depictions is also reminiscent of Max Ernst’s conjoined amoebic figures in paintings such as The Kiss (1927). ↩

- The shapes in PH-674 (1944) reference the bones of intertwined couples as well. ↩

- David Anfam, “Repeat/Recreate: Still’s Multiplying Vision,” Repeat/Recreate: Clyfford Still’s Replicas, exh. cat. (Denver: Clyfford Still Museum Research Center, 2015), 52. Anfam relates this image, with its “twinned dark simulacra,” to Still’s “almost obsessive tendency to group his motifs in pairs,” a trend that imbues some of these images with disquieting attributes of the uncanny. ↩

- “David Anfam on Abstract Expressionism,” abstract critical (December 12, 2013) http://abstractcritical.com/note/david-anfam-on-abstract-expressionism/. ↩

- O’Neill, 180. ↩

- Freeman, 66. ↩

- The drawing is PH-555, 1943. Oil on paper, 19 7/8 by 25 5/8 in. (50.4 x 65.1 cm). Still made two versions of the painting modeled after this small study, PH-235 (1944) in the Clyfford Still Museum collection, and PH-671 (1944), which belongs to New York’s Museum of Modern Art. As Still explained, “(Sometimes) the importance of an idea or breakthrough merits survival on more than one stretch of canvas.” ↩

- Thomas Kellein, ed. Clyfford Still 1904–1980, exh. cat. (Munich: Prestel-Verlag, 1992), 149. ↩

- Still executed a closely related composition as a 108 x 92 in. oil on canvas, PH-379, 1950 (1950-K-No. 1). ↩

- Clyfford Still, letter to John Elmer Still, ca. 1953. Clyfford Still Museum Archives. ↩

- Clyfford Still, letter to Weldon Schimke, 1927. See note 22. ↩

- Harold Rosenberg, who introduced the term “action painting,” later complained about misreadings of it. Action painting “is not a letting go, a surrender to instantaneity, except as a ruse,” he insisted. Automatic drawing, however, was a source of inspiration for several of the first-generation Abstract Expressionists—notably Barnett Newman and Mark Rothko—although Still rejected the theoretical framework underpinning of these investigations. See The Interpretive Link: Abstract Surrealism into Abstract Expressionism, Works on Paper, 1938–1948, exh. cat. (Newport Beach, CA: Newport Harbor Museum of Art, 1986). ↩

- Freeman, 72. ↩

- Clement Greenberg, “American-Type Painting,” Art and Culture: Critical Essays by Clement Greenberg (Boston: Beacon Press, 1961), 211–12. ↩

- Ibid., 221. ↩

- Raymond Parker, quoted in Irving Sandler, The New York School: The Painters and Sculptors of the 1950s (New York: Harper and Row, 1978), 11–12. ↩

- Robert Hughes, “The Tempest in a Paint Pot,” Time (November 26, 1978), 105. ↩

- Greenberg, 226. ↩

Citation Information

Chicago

Failing, Patricia. “Rendering the Sublime.” In Clyfford Still: The Works on Paper. Denver: Clyfford Still Museum Research Center, 2016. /worksonpaper/how-to-render-the-sublime/.

MLA

Failing, Patricia. “Rendering the Sublime.” Clyfford Still: The Works on Paper. Denver: Clyfford Still Museum Research Center, 2016. 1 Nov. 2016 </worksonpaper/how-to-render-the-sublime/>.